I’m in the midst of translating a book written by Spanish dancer Vicente Escudero, Mi Baile (My Dance), originally published in Barcelona in 1947. I first discovered this dancer while researching the intersections between flamenco dance and art in the early and mid-twentieth century. While Escudero was lauded as the preeminent male Spanish dancer of his time, he is little known today outside of Spain. In fact, I was appalled to discover that his entry in English Wikipedia currently has the following heading: “The topic of this article may not meet Wikipedia’s notability guidelines for biographies. Please help to establish notability by citing reliable secondary sources that are independent of the topic and provide significant coverage of it beyond its mere trivial mention. If notability cannot be established, the article is likely to be merged, redirected, or deleted.”

At the peak of his career in the 1920s and 30s, Escudero was at the cutting-edge of the dance world. During an unprecedented 1922 performance at the Parisian Salle Pleyel, Escudero danced to the rhythm of two engines. He wrote in his autobiography how he had become so obsessed with the art of the Parisian avant-garde that he was inspired to translate their vision into dance: “So one night I dreamt I was dancing to the sound of two engines and shortly afterwards I made the dream come true, putting it on stage at Salle Pleyel in Paris, in a concert where I presented a gypsy-flamenco dance, accompanied by two dynamos of different intensity. By breaking the straight line produced by the electric sound, I composed the plastic-rhythmic combination I had intended and which I felt represented the fight between man and machine, between improvisation and mechanical technique.”

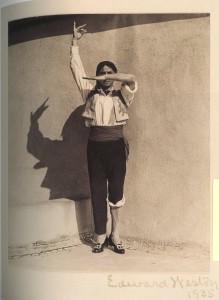

Perhaps attracting the attention of the avant-garde with his machine age performance, Escudero became the subject of the work of several important modernist artists, including Francis Picabia, Edward Weston, Man Ray, and Edward Steichen. In this photograph by Edward Weston, shot in Los Angeles in 1935, Escudero has rolled up his left pant leg to create an asymmetrical appearance and he stands in a pose that is neither flamenco nor classical in style. Holding his left arm in such a way that it shoots horizontally across the plane of his face, we have the feeling that Escudero is crafting an image of himself as what could only be described as a Cubist dancer.

Perhaps attracting the attention of the avant-garde with his machine age performance, Escudero became the subject of the work of several important modernist artists, including Francis Picabia, Edward Weston, Man Ray, and Edward Steichen. In this photograph by Edward Weston, shot in Los Angeles in 1935, Escudero has rolled up his left pant leg to create an asymmetrical appearance and he stands in a pose that is neither flamenco nor classical in style. Holding his left arm in such a way that it shoots horizontally across the plane of his face, we have the feeling that Escudero is crafting an image of himself as what could only be described as a Cubist dancer.

I feel lucky that I was able to find a copy of Escudero’s book, Mi Baile, that was signed by the author himself. My copy was dedicated to a man named Coppicus, who, I discovered while translating the text, was none other than Escudero’s dance partner, Antonia Mercé “La Argentina’s” New York city manager. Escudero has transformed his signature into a dynamic flamenco dancer. The “V” of Vicente swoops across to form the uplifted arms, while the “i” angles to form a broken torso. An elongated “c” becomes a leg shooting backwards, while the “E” becomes the second leg, firmly positioned on the dance floor. The rest of the letters in the signature lie across the outstretched leg. Olé!