Paris Arcades

In the decade before his death in 1940, Walter Benjamin became obsessed with the arcades of Paris – those glass-covered walkways that branch off the boulevards, plunging the pedestrian into an alternative universe, just as magical as Harry Potter’s Diagon Alley, but in a more sophisticated way. The arcades, or in French passages couverts, originated in the early nineteenth century, capitalizing on the use of modern materials like iron and glass for skylights. Charming shops – toy stores, confectioners, gift shops, and restaurants – effuse their wares on either side. They offer a down-the-rabbit-hole experience. Ducking into an arcade provides not only a refuge from the rain, but also from the chaos of the streets. There is a kind of stillness in these spaces. Benjamin thought of them as cathedrals to the commodity, but I think he was bewitched by them all the same. They are precursors to the world exhibitions of the 19th and early 20th centuries, what Benjamin calls “places of pilgrimage to the commodity fetish,” as well as, of course, the modern department store and shopping mall. The viewer can peruse items for sale in total comfort, safety, and luxury – shielded from the elements, protected from the noise of the streets, light pouring down from the skylights above and from the stores on either side, heels clicking succinctly on the patterned marble tiles.

The arcades are my first experience of Paris. After depositing my luggage at the hotel, I set off on my first adventure. Not having the strength to approach the Louvre, I became a flâneur (flâneuse?) instead. I happened upon the Passage Jouffroy, which branches North off the Boulevard Montmartre. What was this? I seemed to be in a corridor with black-and-white marble-tiles below and a continuous arched iron-and-glass skylight above. Acorn-shaped lamps dangling from iron tendrils jutted out on either side. At the far end of the arcade was a clock, embedded in white stucco. The shops on either side held curiosities, such as a toy store laden with dollhouse miniatures, mobiles made of paper clouds, sets for shadow plays, and a dappled hobby-horse presiding at the entrance. Another shop window tempted me with plump chocolate treats, while another was decorated in Carnival masks and silver figurines dressed in 18th century gowns. Around the corner was the entrance to an establishment announcing itself as the Musée Grévin. Searching in my guidebook, I discovered that this was a wax museum founded in 1882. The theatrical wood relief above the doorway featured several of the characters displayed within, including Napoleon with his hand tucked inside his coat.

The arcades are my first experience of Paris. After depositing my luggage at the hotel, I set off on my first adventure. Not having the strength to approach the Louvre, I became a flâneur (flâneuse?) instead. I happened upon the Passage Jouffroy, which branches North off the Boulevard Montmartre. What was this? I seemed to be in a corridor with black-and-white marble-tiles below and a continuous arched iron-and-glass skylight above. Acorn-shaped lamps dangling from iron tendrils jutted out on either side. At the far end of the arcade was a clock, embedded in white stucco. The shops on either side held curiosities, such as a toy store laden with dollhouse miniatures, mobiles made of paper clouds, sets for shadow plays, and a dappled hobby-horse presiding at the entrance. Another shop window tempted me with plump chocolate treats, while another was decorated in Carnival masks and silver figurines dressed in 18th century gowns. Around the corner was the entrance to an establishment announcing itself as the Musée Grévin. Searching in my guidebook, I discovered that this was a wax museum founded in 1882. The theatrical wood relief above the doorway featured several of the characters displayed within, including Napoleon with his hand tucked inside his coat.

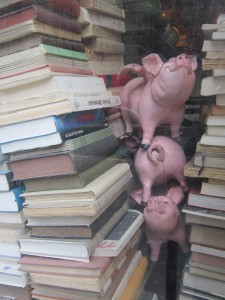

Strolling around the streets of Paris, I soon realized that the arcades were not the only sites with charming shop windows. I happened upon a sizeable store with a collection of taxidermied birds, mostly owls, perching on branches. It made me reconsider my opinion of the French until I noticed a discretely-placed sign in the window that explained how all of the animals for sale in this store had died of natural causes. Perhaps my favorite shop was situated across the street from the Bibliothèque Nationale. Its window was loaded – top to bottom – with stacks of old books. Wedged into a crevice between the stacks were three winged pigs, their pink paint chipped and scratched. One had his curly tail poking at the street, while the other two were grinning at me. It occurred to me that this might be some verbal/visual game invented by the shopkeeper. One possible solution: “I will have all these books organized when pigs fly!”

Strolling around the streets of Paris, I soon realized that the arcades were not the only sites with charming shop windows. I happened upon a sizeable store with a collection of taxidermied birds, mostly owls, perching on branches. It made me reconsider my opinion of the French until I noticed a discretely-placed sign in the window that explained how all of the animals for sale in this store had died of natural causes. Perhaps my favorite shop was situated across the street from the Bibliothèque Nationale. Its window was loaded – top to bottom – with stacks of old books. Wedged into a crevice between the stacks were three winged pigs, their pink paint chipped and scratched. One had his curly tail poking at the street, while the other two were grinning at me. It occurred to me that this might be some verbal/visual game invented by the shopkeeper. One possible solution: “I will have all these books organized when pigs fly!”