Gaga for the Louvre

During my latest trip to Paris, I tried to fit in as much art as possible, which ended up being only a small fraction of what was available, given the fact that I was primarily there as an invited speaker for a conference on Joseph Cornell, and only had three extra days to devote to sightseeing. As much as Cornell loved French art and culture, he never traveled beyond the East Coast of the United States. Crying in front of the Corot’s and the Millet’s at the Musée d’Orsay, I had to remind myself that Cornell would not have had this experience. Whatever French art he saw would have been experienced through books (the kind of grainy publications of the 40s and 50s) or the collections of the Met. Swimming through a sea of bodies in the French Neoclassical and Romantic galleries of the Louvre, I encountered the curled toes of Brutus from David’s Lictors, clenched with a stern self-loathing following his decision to execute his sons. I discovered a dog slumbering in the bushes of Girodet’s Sleep of Endymion, a feature I was barely able to discern in the dark reproductions. And I could almost feel the waves buoying up the flailing bodies, clinging to life, aboard Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa. In the History of Art & Architecture department at DePaul, plaster copies of Michelangelo’s slaves are stationed amidst the file cabinets in the main office and became a commonplace feature of my workplace, but confronted with the originals at the Louvre, I felt myself melting at their erotic intensity: hunkered down or luxuriating in marble. Wasn’t this simply too much energy for one building to contain? I felt myself bursting. There were paintings I took pictures of – I see the record of them here on my camera – and now I don’t even remember having seen them. Ingres’ Grande Odalisque: I asked a stranger to photograph me in front of it, and now I don’t even recall that moment. I was wafting along.

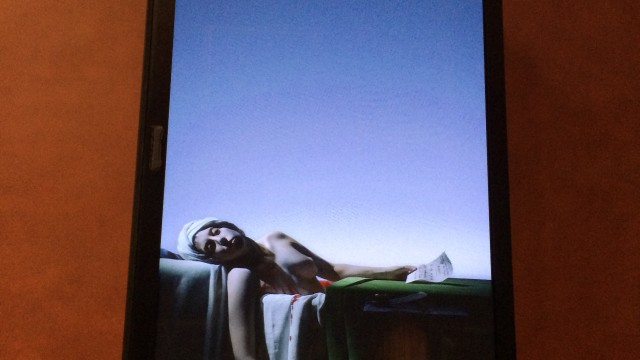

And then an eery reminder of the 21st century popped the bubble of my elation: there was David’s Death of Marat as performed by one of my contemporaries, glowing on a flat-screen TV. I read the wall plaque: Robert Wilson staged a recreation of David’s masterpiece using Lady Gaga. Having taught this painting so many times as part of my lecture on the art of the French Revolution, I couldn’t help but compare Wilson’s version to the original, as I remembered it. Wilson’s piece was glowing and I kept glancing at the black frame. I was waiting for the image to change, like on a TV, but it didn’t. As an image on a monitor, it lacked the sensuality of a painting, but it also lacked the dynamism of a video. Bill Viola’s Quintet Series is fascinating because the figures shift, but so slowly that it almost isn’t apparent. But Lady Gaga just laid there. Slumped over. And then of course there was the breast. That reminded me of Duchamp’s Étant Donnés, and the plastic quality of her body, like a figure in a wax museum. This contemplation of Wilson’s piece made me realize what I love so much about the original: David paints the exact moment of Marat’s final breath – he has just been stabbed, we are even given the point-of-view of the murderer, Charlotte Corday, and as we gaze down at him, Marat breathes his last. But here is Lady Gaga, posing. Lips pressed closed. Clutching her quill. I imagine she will open her eyes and say to Wilson, “Was that good?”

Wilson’s work has become less powerful, less concentrated on the essentials of art, less intimate — while not being particularly amusing. The annoying celebrity add-on is dreadful for the desired emptiness of Wilson’s attractive and intelligent art, and his work does not bode well for art in the classical tradition of high minimalism.